Jody Macgregor

Curated From www.pcgamer.com Check Them Out For More Content.

Some horror games are set in spooky castles, abandoned mental asylums, derelict spaceships, or circuses with an unwise hiring policy regarding murderclowns. Others are set in less outlandish locations, like suburban streets, shopping malls, hospitals, schools, or ordinary homes. I find the second kind have the most impact, haunting my thoughts long after they’re over like a picture I shouldn’t have looked at on the internet.

WHY I LOVE

In Why I Love, PC Gamer writers pick an aspect of PC gaming that they love and write about why it’s brilliant. This week, Jody appreciates homey horror.

The Silent Hill games are especially good at this, and have made me feel even more ambivalent about hospitals than I already did. Hospitals are stressful places to begin with, but Silent Hill 2 also visits places as comfortably mundane as apartment buildings, a nightclub, a historical society, and even a bowling alley, all of which it imbues with terror. A brief scene in a cemetery turns out to be a rare moment of safety. Though eventually Silent Hill 2 descends into a dark underground prison, its horrifying finale is saved for somewhere else: a holiday resort on a lake.

The scariest things in Silent Hill 2, whether geometry-faced butchers or mindblowing revelations, are accentuated by the ordinariness of their backdrops. We anticipate creepy stuff going on in gothic mansions, that’s the whole point of them, but the worst thing you expect to encounter in a bowling alley is a 7–10 split. Silent Hill takes innocuous places and peels their skin back until the walls bleed with rust and the floors flake away to reveal fragile chainlink over bottomless pits.

What the chuck?

I used to live in an apartment building with an evacuation map on the wall just like the maps in Silent Hill and it freaked me out every time I saw it, but there’s a risk when horror games choose innocuous settings. If players aren’t personally familiar with them, they won’t have that element of recognition.

I wasn’t frightened by the animatronic mascots in Five Nights At Freddy’s not because I’m so very brave, but because I didn’t grow up in a country where fast food restaurants have mechanical hosts. There’s no Chuck E Cheese in Australia—they tried in the 1980s under the name Charlie’s Cheese because “chuck” means vomit here, but even with the name changed it didn’t catch on. Freddy’s is as exotic as any Transylvanian castle to me, and doesn’t inspire lasting dread.

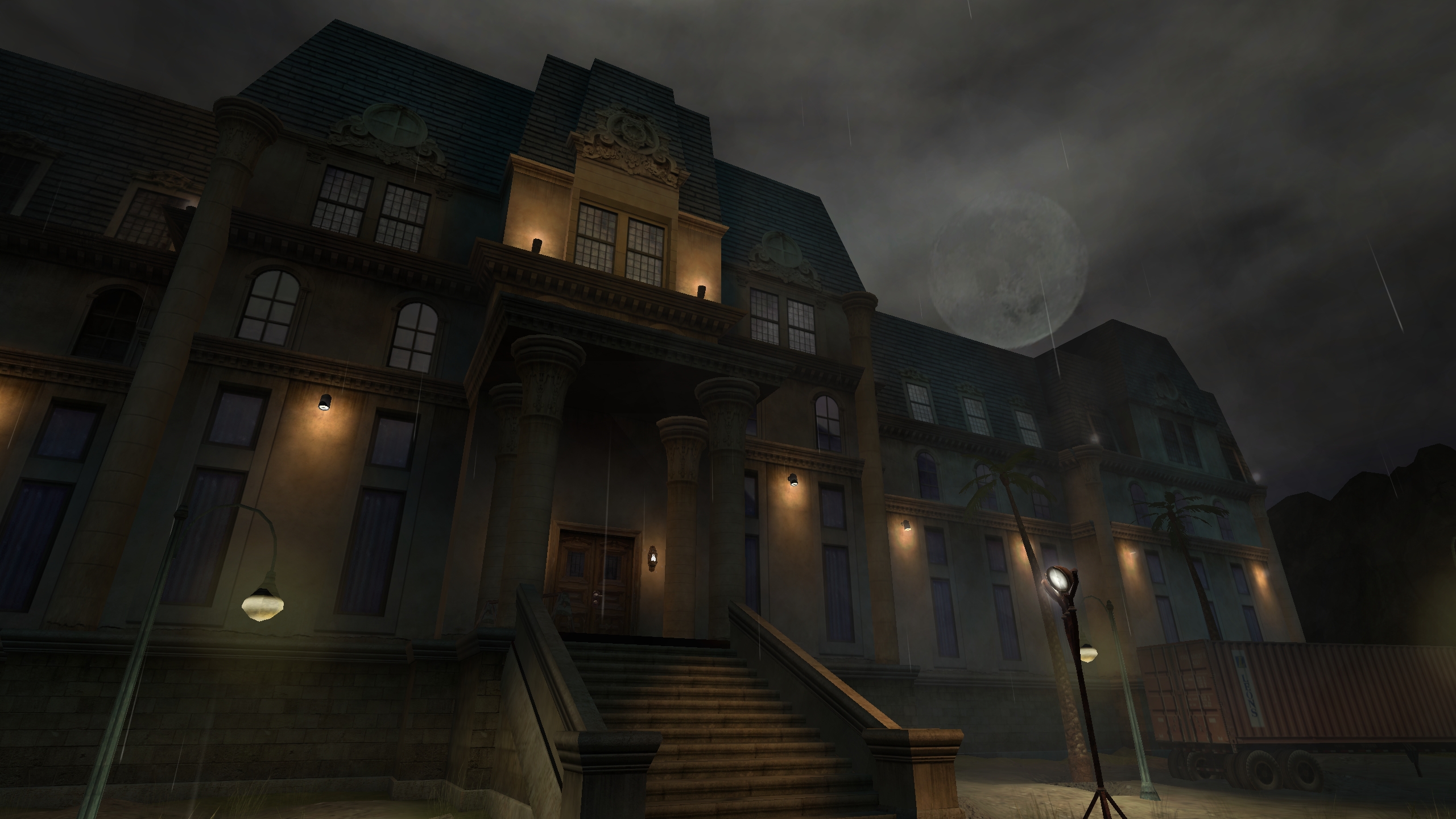

More often than not it’s an effective technique, though. The most frightening places in Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines and Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth are regular old hotels. Both lull you into a false sense of security. In Dark Corners you can lock the doors of your hotel room before bed, but nothing will stop the locals from kicking their way in to kill you in your sleep, forcing you into a heart-hammering rooftop escape that culminates in the most frightening thing videogames can throw at you: precise first-person jumping.

Meanwhile, Bloodlines makes you a vampire with superpowers, so you expect to have nothing to fear from an empty hotel, even if it’s haunted. But when you get there the well-paced scares—popping lightbulbs, a distant child’s laughter, figures running past you down corridors but disappearing when you round the corner—combine with the mechanical worry of your blood meter slowly emptying because there’s nobody around to feed on to create a singular moment of traditional horror. In a game that’s otherwise about confronting the personal horror of your own monstrous nature, it’s quite the achievement.

Alienation station

That’s not to say more obvious locations don’t have their place in horror games. The Shalebridge Cradle in Thief: Deadly Shadows is a perfect example: a mental asylum that is also a haunted orphanage, one cliché draped on another like a sheet over a corpse. It still manages to be memorable through a combination of claustrophobia, excellent enemy design—those twitching, cage-headed lunatics—and a command of light and darkness that benefits it both as a stealth game and an engine designed to freeze your blood solid.

Yet even in more typical horror settings, a dose of normality helps. The grisly spaceship Ishimura from Dead Space is frightening at first, but after a few hours there I learnt to expect necromorphs bursting from its blood-soaked vents. Though Sevastopol Station from Alien: Isolation was also floating helplessly in space and an alien was just as likely to slither out of the ceiling in a hall full of graffiti, it never stopped being scary. Its rooms were rather less full of corpses and rust, often antiseptically well-lit, with ordinary desks, old computers, and executive toys. It felt like an office for a paper supply company, all square edges and coffee cups, accentuating the sleek, gangling silhouette of the alien and its elemental wrongness.

They say familiarity breeds contempt, but in horror contempt is useful. Familiar locations trick us into thinking we know what to expect, and there’s power in yanking those expectations out from under our feet to reveal the thin chains separating us from the abyss.