Halloween may have passed but that won’t stop Nicky and Steve from taking a deep dive into the OG of horror manga, Shigeru Mizuki.

Akuma Kun (2023) is available through Netflix, GeGeGe no Kitarō (2018) is available through Crunchyroll, NONONBA and Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths are both available through Drawn & Quarterly.

Content Warning: Depictions of War and Death!

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the participants in this chatlog are not the views of Anime News Network.

Spoiler Warning for discussion of the series ahead.

Nicky

Elohim, Essaim. Elohim, Essaim. I entreat thee. Spirit from the cyber realm, awaken from thy slumber. Appear from the wires, in the name of the editor of This Week in Anime, I command thee!

Steve

Let this be a lesson to you, folks. Watch too much anime and you turn into a demon. Happens to the best of us.

You’d think all that haunting we did in October would’ve exorcised the spooky bug out of our systems but it turns out the scares are just a part of our DNA as anime fans. Sorry for not “giving up the ghost” just yet, but this week we’re honoring the ambassador of ghost stories, Shigeru Mizuki.

Now TWIA superfans (all dozens of you) will recall this isn’t our first brush with Mizuki’s oeuvre. We briefly covered the newest

GeGeGe no Kitarō series when it debuted five years ago and now we’ve got a reboot/sequel of

Akuma Kun to dig into. So we figured we’d take this opportunity to talk more broadly about Mizuki as an artist. While he hasn’t had quite the same level of penetration into the Western sphere as some of the other manga giants, he’s no less of a gargantuan figure than a Tezuka or a Nagai—and he’s certainly a spookier one.

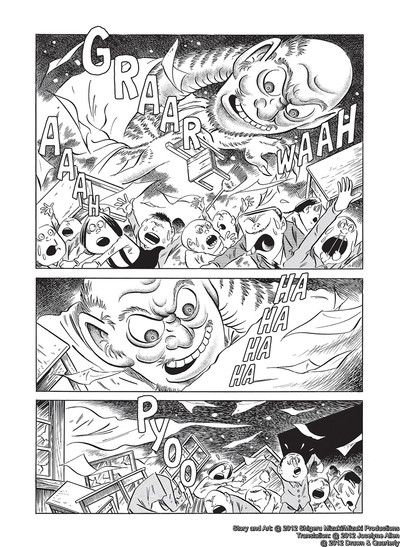

The legend of Mizuki’s career is far greater than most of us could’ve imagined and although he passed of a heart attack in 2015, he lived to the ripe old age of 93, spending his entire life dedicated to studying all kinds of gremlins, ghoulies, and ghosts known traditionally as “yokai.” Since childhood, he had been fascinated by folklore and fairy tales. He is the one who popularized the supernatural genre as it exists in anime and manga today. It’s really hard to imagine a world where ghost stories weren’t a keystone of Japanese media, but much of that is largely due to Mizuki’s creative interpretations. This can be found in GeGeGe no Kitarō singing along to that classic opening theme about how fun it would be to play around with ghosts who never get sick, go to school, or go to work.

There are good arguments that Mizuki’s fascination with and portrayal of yokai had the most profound impact on how we now visualize and interpret them. If you were a kid in the ’60s, you probably weren’t learning about yokai from reading old scrolls. You were seeing them in the latest issue of GeGeGe no Kitarō. That effect trickled down across the decades, and it made Mizuki Japan’s most important ambassador of that branch of folklore in a century otherwise preoccupied with modernization.

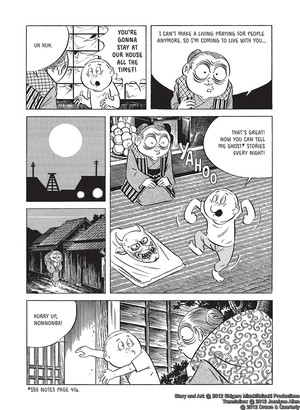

Mizuki’s work is also greatly informed by oral tradition. Before he became a mangaka he worked doing shadow puppet plays or “kamishibai,” and before that, he learned everything he knew about yokai from the old lady who took care of him, whom he nicknamed Nononba. Outside of his manga career, he also worked as a world historian, made encyclopedias cataloging yokai, and traveled to different countries in the academic pursuit of the fantastic realm.

Yet, very little of Mizuki’s storied contributions are available in English. Even though there’s a GeGeGe no Kitarō for every decade, only the latest one is available on streaming platforms—and now with the most recent Akuma Kun anime provided by Netflix, that means we now have a whopping TWO series inspired by Mizuki available to us. Furthermore, the availability of Mizuki manga in English hasn’t faired much better, with only a few titles translated, despite being about as prolific and influential as the one people call the “God of Manga,” Osamu Tezuka. This means there are hundreds of works we’ll never see in English. For example, the Akuma Kun that serves as today’s series inspiration still doesn’t have a manga license in English, at all! Making many of the references difficult to parse. This is the second Akuma Kun, with the first one being his foster father!

I’m not gonna pretend to understand the machinations of

Netflix licensing a sequel to a 30-year-old anime you can’t find on the platform, but

Akuma Kun‘s continuity isn’t too difficult to glean from context. And from matching hairstyles and magician outfits.

Anecdotally, I had never heard about Shigeru Mizuki growing up. Thankfully, though, with the manga boom of the 2010s, we got some of his works translated—particularly the historical ones—so things aren’t quite as dire as they used to be.

It didn’t stop me from enjoying the show. I think it says a lot about Mizuki’s originality that he laid the ground for Monster of the Week stories and that his worldview can still be carried out post-mortem through the supervision of his son. The new series also makes just as many references to the ’89 anime—and both series have been helmed by

Junichi Sato, a name which some anime fans might recognize as he’s been working with

Toei for a long time, especially on a little show called

Sailor Moon, which also featured quite a bit of monster of the week plots.

They also sneak in a little homage to Mizuki himself. It’s cute.

Mizuki has also inserted himself into his series several times, as beyond fiction he’s also produced an autobiography,

Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths, depicting his childhood in the 20s with

NonNonBâ and his deployment in New Guinea during WWII that cost him his arm. Mizuki is a fascinating figure as so much of his work stems from his personal life and lived experiences outside of being a beloved cartoonist. So much so, Steve and I both agreed that it wouldn’t be sufficient to talk about him using only anime as a reference point, and we made the rare move of reading these manga detailing his life.

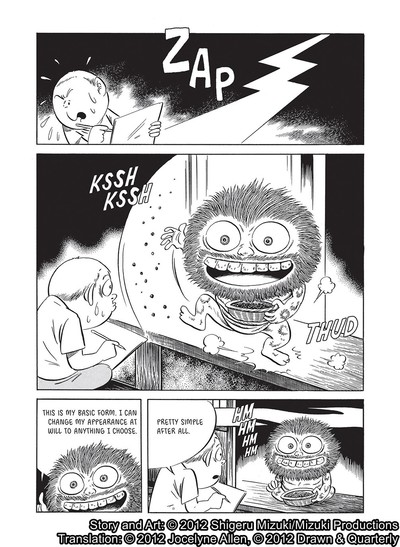

And the first thing that jumps out to me is how ridiculously talented he was. You can tell he taught himself how to do a lot of things because his style is so unlike any other mangaka—contemporary or otherwise. The character designs especially are so cartoony and expressive. He doesn’t even need to “wow you” with any yokai.

His drawings may be very cartoony and simplistic in a way that’s reminiscent of his period but the realism of his backgrounds is impressive. As if the reality makes the abstract characters stand out. In

NonNonBâ particular, it felt like a really good way to depict childhood memories as the characters feel so lively. There’s no doubt that something like this happened and that the titular

NonNonBâ was as much of a character as she has been drawn.

Not to mention the depiction of Shigeru’s family, the residents of his neighborhood, and the whole era of living in the boonies before modern conveniences. It feels like you’re seeing events happening in front of you.

It’s authentic in the way you’d expect from someone whose memories and imagination are equally vivid. Though, it is funny when he introduces an early crush and draws her with those big watery doe eyes. She looks so out of place (and purposefully so, to be fair).

The realism also extends into the fantastical in that there’s a sense that the few encounters with Yokai did happen or at least felt real at the time. It’s up to interpretation whether events are a product of that trademark childhood imagination—but as an adult Shigeru has spoken that he’s the foremost believer in the demons he draws, citing, that the only reason you don’t see them as often now is due to the light pollution created by modern cities.

He’s so good at tapping into that part of a child’s psyche. They don’t understand everything, but they understand enough to come up with the wildest ideas and explanations, especially when guided by as committed a teacher as

NonNonBâ. And through this, he gives form to a wonderful collection of weird guys.

Look at that dude. I love him.

The fantastic elements also create the heart of the book, as it wasn’t easy living as a kid without money, TV, or modern medicine. Many children of Shigeru’s age passed of illness, are brutalized, or even sold into slavery, all while the adults struggle to figure out how to put food on the table. Shigeru’s cousin dies of tuberculosis but the deep sorrow is weakened as Shigeru imagines the paradise she passes onto. Much of traditional superstition was not only moralistic but also a way of coping with grief or various maladies, much like religion.

NonNonBâ is frequently beautiful but never varnished. While the politics and injustices of the time might not always directly impact his character in the manga, they all inform a conclusion about coexistence.

Besides, if you’re a kid with nothing to do why wouldn’t you just start daydreaming about monsters around you? That wart on your thumb is a demon that made you cheat on your test or that shadow in the sea is a scary suiko. We need our imaginations to keep everyday life interesting.

Today’s Sakaiminato has been modernized and has even become a popular tourist spot celebrating Mizuki’s imagination, with a museum, a decorated train, and a walkable road covered in hundreds of bronze statues of Mizuki’s most memorable characters—making it much easier for today’s children to imagine that yokai are right there.

While the characters in

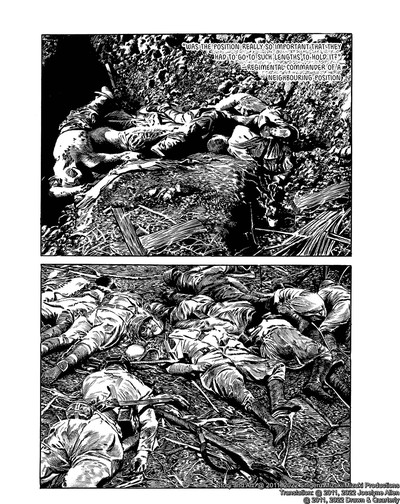

GeGeGe no Kitarō may be his most lasting legacy, Mizuki didn’t only focus on twisted yokai tales for children. He dipped into more “serious” topics, although “dipped” is probably the wrong verb when one of those projects is a multi-volume survey of the entire Showa era. Like Tezuka, he also tackled the life of Hitler. And it’s no surprise he kept returning to World War II, considering he was deployed during the war to an upsettingly bleak mission chronicled wryly in

Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths.

Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths is a 90% True Story about a small platoon in Japan stationed off the coast of what is now New Guinea and commanded to embark on a suicide mission which none of them survive (though in reality about 80 of them lived). It is an unglamorous yet darkly humorous telling compared to most fictionalized accounts. The nobility of death that overtakes the dignity of the living is greatly emphasized as war’s greatest irony. There’s nothing heroic or enviable about these men struggling to survive without proper food and hygiene in such a dangerous and hostile environment.

Yeah, the writing and art practically scream about the absolute absence of anything resembling honor in that situation. It’s a war narrative refreshingly bereft of any semblance of propaganda. Mizuki draws and inks an actual hell. His comrades die quickly and unceremoniously. His superiors are abusive and unqualified. It’s a shit show (sometimes literally), and it takes so many lives for no good reason.

Like his other works, his grasp of caricature is unmatched here, but it hits differently when you start seeing these characters explode into gory chunks.

It’s also surprisingly very funny and human, most of the subject matter is very crude, gruesome, or gross, but it’s very honest in the way that you might talk about something that happened to you or that people might focus on humor to cope with the situation they are in—or the fact that humans (and life in general) are honestly just somewhat flawed and gross in a universal way. Much of the abuse taken is portrayed as slapstick cartoon sound effects.

Take a step back and you realize that he was getting beat up by his superior officers in those scenes. But you can also understand that, in retrospect, those moments must have seemed all the more cartoonish in contrast to all the death and hopelessness that would ensue. That black humor spoke to me. I’d count this as one of the most affecting WWII narratives I’ve ever read.

I think it also humanizes the other people that were there, like

NonNonBâ many of the characters in

Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths feel real and lived-in. Mizuki was even sympathetic to his garbage superiors because he didn’t think they deserved to die in such a “noble” fashion. It also emphasizes that life is just kind of weird, some of the funniest moments are just average getting screwed over by nature like anyone would consider it weird and tragic to be suffocated by a fish. It’s a delight to discover a cache of bananas when your most common battles are against hunger and malaria.

It’s that kind of unabashed perspective that makes me believe that most of this happened. I believe that soldiers sing silly songs about showing alligators their junk—just to stave off the fear of dying, boredom, or homesickness. Despite being a depressing situation, it’s not difficult to read. Its commentary still rings true. The most unbelievable aspect about it is that Mizuki was able to publish this story in 1971.

It’s illuminating. Oppenheimer’s release caused the resurfacing of many (bad) arguments about the decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki—some of which were rooted in the idea that Japan’s military and citizens were drones that would never surrender otherwise. This was self-evidently untrue, but it’s especially hard to argue against a first-person account that flatly depicts a protagonist who thinks being ordered to do a suicide charge is stupid and pointless.

Mizuki also depicts the natural landscape of New Guinea as beautiful and awe-inspiring, even when tainted by the stench of death. I think the connection between Mizuki’s fiction and nonfiction is the love of life and nature. He stated that he managed to revisit New Guinea and that most of the backgrounds are a combination of photo and memory.

Also worth emphasizing that he lost his left arm in the war, which is important context both for his reflections as depicted in Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths and for his unparalleled technique despite that loss.

Although there are no yokai in

Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths, its portrayal of war is terrifying. However, don’t assume that ghosts are irrelevant, as Mizuki believes the ghosts of his comrades were driving the heat of his passion whenever the topic of war comes up.

The man was passionate, but he also described himself as spending his life “half-asleep,” wryly contrasting his more laid-back work ethic with Tezuka’s all-nighters. Tezuka, notably, died at age 60, while Mizuki was active into his 93rd year. There’s value in taking it easy.

Still, his passion for life seems like a big part of his influence as the yokai characters he creates are just as much living things—often emulating nature, animals, or even people. Many of them are not inherently good or bad, and his human characters are equally capable of great or malicious deeds. Even more modern interpretations of his stories carry this sort of ambiguity and it’s why so many of his characters remain colorful.

A recurring refrain in the new Akuma Kun is that the demons being summoned are neither good nor evil. They can help and they can hurt, but for the most part, they adhere to the contracts and agreements of those who summon them. They are, in essence, bound by rules. They’re natural forces. We can try to bargain with them but our relationship starts and stops with whether or not we show them the proper respect.

They’re also simply attracted by human emotions and watching things play out rather than simply acting on them. My favorite episode of the new

Akuma Kun was episode four where it’s ambiguous whether the two directors hated each other or cared about each other—cuz I can’t resist getting sappy over art with other people!

The show doesn’t always hit the level of thoughtfulness it’s aiming for (and to be fair, I have no idea how that compares to the original Akuma Kun series), but yeah, moments like that one are where it’s at its best. The Mizuki manga we sampled are rich and three-dimensional and that’s what these adaptations should aspire to.

Similarly, I do appreciate that it doesn’t hold back on a lot of subjects. I thought the previous GeGeGe no Kitarō anime handled many mature and topical themes (like YouTubers running into traffic), but Akuma Kun has some very dark material for what is a legacy family property. However, I also consider that is very much in Mizuki’s spirit because even his more kid-oriented stuff took his audience seriously and never tried to shelter the reality of things—despite being so fascinated with fantasy. I hope that’s something that continues as we see more work celebrating his 100th birthday. Other than Akuma Kun, Toei is also planning an upcoming GeGeGe no Kitarō prequel film.

We all love a children’s author who respects the depth of a child’s psyche—and one who respects the rest of his audience too. I have to imagine that attitude was in part ingrained in him by

NonNonBâ. On one hand, her stories usually dovetail into a useful parable a child could learn from, but on the other hand, she also treated him like an equal and handed down these stories from one teller to the next. Mizuki, in turn, did his part, so it’s now our duty (and privilege) to keep this cultural memory of goofy spectral fellas alive.

I think that says so much about the reason we tell stories. We tell stories to teach, we tell stories to fantasize, and we tell them to record and remember our experiences. Mizuki started creating his own stories at a young age and it’s because of his life that we all get to enjoy them. I would like to enjoy more of Mizuki’s original stories in English as we continue to get anime that are inspired by him. I had a fantastic time with

Akuma Kun,

GeGeGe no Kitarō, and Mizuki’s autobiographical works—and I came to greatly admire him as a storyteller. It is a shame he’s so unknown in English, but I believe stories are magic spells. Once cast, they will only grow more powerful through every person they touch. As a man who was so engrossed by notions of monsters and myth,

Shigeru Mizuki certainly created a magic all his own.