Curated From www.animenewsnetwork.com Check Them Out For More Content.

X-Men‘ 97 has now concluded its stunning first season, and those ten episodes highlighted the best and worst of Magneto — a man who’s been both the X-Men‘s nemesis and leader.

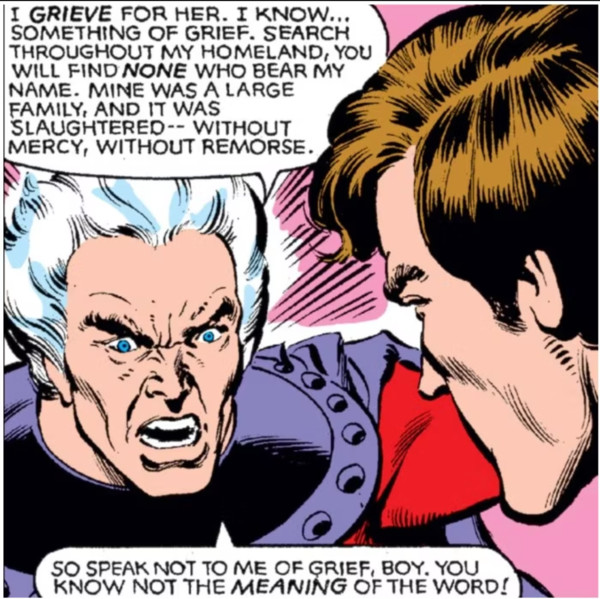

Introduced at the very beginning of X-Men in Stan Lee and Jack Kirby‘s 1963 debut issue, the “Master of Magnetism” has changed a lot in his sixty years of existence. What remains consistent is how he fights for beleaguered mutants against humanity, among whom there are no innocents, he argues. Chris Claremont, writer of X-Men for 16 years, revamped Magneto into an anti-hero whose misanthropy and militancy came from surviving the Holocaust.

Since then, Magneto has existed on the thin line between tyrant and revolutionary, with different creators pulling him to different sides in an endless cycle. X-Men ’97 features him traversing both ends. He starts the show having inherited stewardship of the X-Men from his best frenemy, Charles Xavier. After the mutant nation of Genosha is wiped out, he returns to believing that tolerance of humans is mutant extinction. By the season’s end, Xavier brings him back around.

There’s a feeling of competition between American superhero comics and shonen manga in fan circles (egged on by memes). Still, both use the same medium to tell adventurous, high-stakes stories. There’s plenty of room to put them in conversation. One manga character cut from the same cloth as Magneto is Scar from Hiromu Arakawa‘s Fullmetal Alchemist, an unsung hero — even by his creator.

Fullmetal Alchemist is, no surprise, about alchemists, and the story questions their responsibility. Knowledge is literally power in the land of Amestris. The Fullmetal Alchemist himself, Edward Elric, says in Chapter 1 that alchemy, rearranging the matter of the world to one’s own will, is like godship. If alchemists claim they can challenge God, then, of course, some would see that as heretical.

Enter Scar, introduced in Fullmetal Alchemist Chapter 5 as a religious fanatic who intends to kill every godless alchemist he meets. Since Scar thinks he knows the will of God, then he can act as its instrument, even lethally. This is motivation enough, but Arakawa doesn’t stop there; Chapter 7 reveals that Scar’s people, the Ishvalans, believed alchemy was blasphemous in the eyes of their creator deity.

Those fears were confirmed after the Amestrian military invaded their land and massacred them with an army of State Alchemists. In retaliation, Scar murders State Alchemists not just for their heresy but to kill them like they killed his brothers and sisters. Once more, this is fantastic worldbuilding; alchemy is a fact of life in Amestris, so its use as a weapon and philosophical spurnings of it would follow, like the science of our world.

It’s easy to compare Scar and Magneto. Both belong to a religious minority and survived a genocide of said group. While Scar retains his beliefs, Magneto does not — “I turned my back on God forever,” he says in Uncanny X-Men #150 (by Claremont and Dave Cockrum), the defining issue that revitalized his character. While Scar believes he is the hand of God and Magneto feels he can’t rely on any such hand after his torturous childhood, both refuse to take organized oppression lying down.

©2024 MARVEL

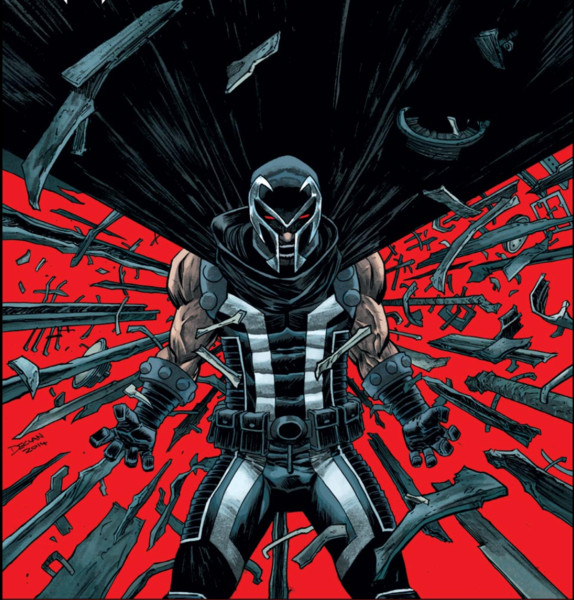

Both men lead violent crusades because the world taught them there is no other way to change it. Their powers reflect their intent to change the world with force; Magneto’s hands can bend metal without moving, while Scar’s right arm is tattooed with alchemic symbols of destruction he can use to eviscerate those in his path.

So, why are Magneto and Scar the villains? When I read X-Men or Fullmetal Alchemist, I feel their anger; doubly so when their characters are rendered in animation, and I can hear the pain and conviction in their voices. How can you not? Their actions are responses to tragedy and continuing injustice. Magneto’s worst suspicions of humanity always come true in genocide after genocide, while Scar is killing war criminals who serve an enduring regime. He’s not innocent (he killed two doctors in delirium after he awoke from the explosion which killed his family, while Edward had nothing to do with Ishval), but his targets have more blood on their hands than he does.

As much as I love both series, I feel a disconnection with how they frame these characters. Scar and Magneto get sympathy, and the fact that their authors deem them worthy of redemption speaks to their depth. This isn’t the lazy trope where the villain “has a point” but also does incongruent horrible things to make the audience root for the hero. Scar and Magneto’s violent actions are intertwined with their ideologies. That the story asserts they need redemption and to change their ways to achieve it is the issue. When Scar meets his former teacher in a refugee camp, he gets a lecture:

“Enduring and forgiving are two different things. You must not forgive the cruelty of this world. It’s our duty as human beings to be angry at injustice. But we must also endure it. Because someone must sever this chain of hatred.”

Beautiful words, and ones that could have come from the mouth (well, speech bubble) of Charles Xavier. But they place the responsibility to break the cycle of vengeance on the oppressed and how they respond to continued suffering. Scar completes his change of heart by literally defeating Wrath, confirming his earlier actions as anger, which begot more anger.

Arakawa drew on Japan’s history with the Ainu when creating Amestris and Ishval, but she (purposefully or not) tapped into the contemporary events of Western Imperialism too. Every iteration of Fullmetal Alchemist invokes the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in depicting the Ishvalan War of Extermination. Nowadays, the images of desert cities turned to rubble and children crying surrounded by explosions evoke the Israeli invasion of Gaza.

© Hiromu Arakawa/SQUARE ENIX

X-Men purposefully parallels civil rights struggles too. Mutants are mostly accepted as a queer allegory these days if an imperfect one. By using characters like Magneto and Scar to represent real struggles, the question becomes: when is it ok for the oppressed to hit back? Why must self-defense come with a loss of the moral high ground?

“Magneto Was Right” has become a meme, repeated by X-Men fans who’ve had the same realization as I. In X-Men‘ 97, those three words are said aloud — not even by one of his fellow mutants, but by a sympathetic human. The Genosha genocide made the future so bleak for mutants, yet it surprised none of them that even the story can’t label Magneto misguided. Fullmetal Alchemist could be an even greater tale if “Scar Was Right” had crossed anyone’s mind but his own.

Now, the unavoidable difference. Unlike X-Men, Fullmetal Alchemist is a finite story with a single author and an ending. Arakawa completes Scar’s arc as one part of her manga tapestry. The Fullmetal Alchemist manga explores the world’s interconnectivity and how humans are the nodes of that push-and-pull. The God of this world, the Truth, is not a cosmic puppeteer but the pooled form of human knowledge and actions. Even if the world is a greater whole, we can’t forget to acknowledge the uniqueness of individuals and neglect our responsibilities to each other.

If Amestrian soldiers like Roy Mustang and Riza Hawkeye must atone for the monsters they became in Ishval, Scar has the responsibility to not let anger over his suffering reshape him. Scar’s arc climaxes with him accepting the reconstructive side of alchemy, reflecting not just how he’s moved on from a path of only destruction, but how he no longer defines his actions as those of God. Any misgivings aside, it is a complete story with a consistent thread to hang on.

© Hiromu Arakawa/FA Projects, MBS

If there’s one hitch in that thread, it’s the 2003 Fullmetal Alchemist anime. Completed by Studio Bones before Arakawa finished her manga, it charts its own path. This makes the collective Fullmetal Alchemist experience more like an American comic franchise, i.e. X-Men, where different series will take the same premise on a unique spin.

I don’t think the 2003 Fullmetal Alchemist is better than the manga or the truer anime Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood, but I find its handling of Scar is more politically palatable — to a point. The Ishvalans are explored more, as is Edward’s complicity as a State Alchemist, or “dog of the military.” This version of Scar, who doesn’t go on the same journey of forgetting vengeance, dies to deal a blow to the Amestrian military and prevent another Ishval-style massacre. His final words?

“A man who inflicts suffering can not rest. His guilty mind won’t allow it. But today, I can finally close my eyes to the living nightmare and lay down knowing that I won’t wake again.”

In the 2003 Fullmetal Alchemist, Scar doesn’t break the cycle of revenge, he completes his part in it and can only find peace in death. His life comes to the conclusion his manga/Brotherhood self expected it to at the beginning of the story.

If we’ve seen Scar walk two paths, Magneto has walked dozens. He’s been spun through Marvel Comics‘ revolving door, handed off to different writers across unending comics and countless adaptations. Many writers come with different perspectives, while the patchwork structure of the Marvel Universe lets readers pick and choose which interpretations are definitive to them.

©2024 MARVEL

Writer Cullen Bunn’s Magneto (published in 22 issues from 2014-2015) features Magneto who is the most like Scar. No Brotherhood of Evil Mutants by his side, no schemes for world domination, just a driven man who walks with a purpose; to eliminate any threats to mutant kind. In making Magneto a lead, Bunn melds the competing interpretations; Magneto is a hero, but a self-righteous and violent one.

Magneto has even defied death which dries the cement of life into a legacy. Al Ewing and Luciano Vecchio’s Resurrection of Magneto (published this year) features Magneto pulling himself up from eternal rest, convinced that his potential for good outweighs his sins and can only be fulfilled if he lives. The comic ends much like Scar’s journey in Fullmetal Alchemist does; Magneto is revived after he finally calms the storms and contradictory halves of his soul, but he won’t stop fighting for his people.

Why do those contradictions exist, though? Because Claremont took the one-note, history-less Magneto who Lee and Kirby made and used that as the foundation for a reasoned foil to the X-Men. In trying to craft an understandable yet misguided character, Claremont — and Arakawa — underestimated how the world their characters were so angry at could prove them right.